Ernie Banks passed away at the age of 83. He will be remembered as “Mr. Cub,” a two-time MVP, Hall of Fame player who never had the honor to play in a World Series.

Banks was a focal point for many kids growing up in the 1960s and early 1970s. Back then, we played baseball all the time. Today, we would have been called “free range” kids since we played outside from dawn to dusk. And baseball was the number one sport. We would play whiffle ball in the back yard, throw tennis balls against imaginary strike zones on garage doors or school walls, and play hard ball in the park.

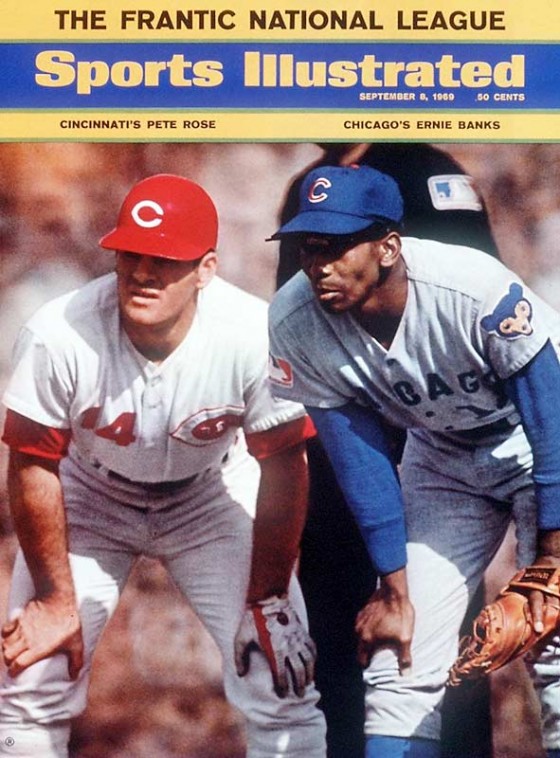

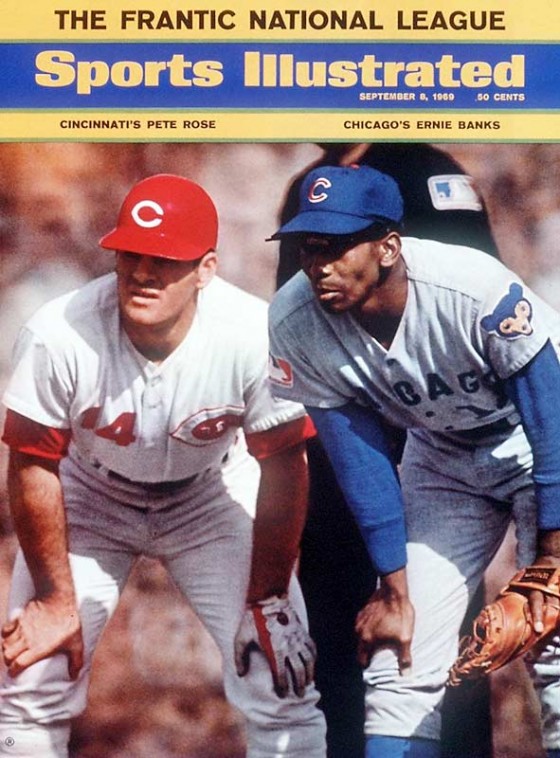

We learned the game by watching players play and listening to the radio broadcasts from guys like Lou Boudreau, a Cub announcer. I have told this story many times. It was the fall of 1969 when I was in elementary school. I sat in the back row. Next to me was a New York transfer student. He was a Mets fan. During that fall, I would hide an Emerson 9-V AM radio in my desk to listen to the Cubs games on the radio. This was going to be the year that would end the curse. The Mets kid would rag me that his team was better, and the banter went back and forth until the Cubs eventually collapsed down the stretch. It was not Ernie's fault, or any of his teammates. The 69 Cubs by coming so close became icons for our generation.

Not everything in life comes up a winner. Failure is an option. That is an important life lesson that is lost for some children today, with participation trophies and helicopter moms.

Banks was the eternal optimist. You could tell that he loved the game of baseball. He was a kid being paid as a adult to play a game. He soaked up the opportunity and blessing of his talent. He was an excellent shortstop, with good fundamentals and solid work ethic. He made the game fun. He wanted to get the ball park each day to play. It was infectious. This is why those Cubs teams were so likable, and the Cub fan base so loyal to their team. Even when they lost, we knew that they hustled and tried their best.

But what we did as kids was to copy the baseball players batting stances, from holding the bat high over one's back shoulder like Bobby Tolan, to the 90 degree left forearm, cocked wrist, and finger dance of a flutist of Ernie Banks. Little did we know the science behind Banks' grip: the lighter the hand pressure on the bat itself, the quicker the bat would go through the zone. Banks had an effortless swing, much like teammate Billy Williams. We always ran home as soon as school was out to see if we could catch a late inning at-bat on the television.

I did get home from school in time to watch Banks hit his 500th home run, a line drive shot into the left field bleachers that made Cub broadcaster Jack Brickhouse go nuts on the call.

We did not care that Banks or Williams or Ferguson Jenkins or whomever was a different color or race. They were our Cubs, and we rooted for them. Later in life when we were taught the history of segregation and the trials that the first black players like Jackie Robinson had to endure just to play our game, we had even more respect for our minority Cub players.

I did have a chance to briefly meet Banks at a Chicago charity function well after his playing days were over. He was still a tall, lanky gentlemen who always smiled and was gracious to the people around him. If modern players need a role model on how to act as a profession, they should be forced to watch a documentary on Ernie Banks. Banks was a one of kind gentlemen, the rare professional who everyone liked and respected, including his opponents. As people remember Mr. Cub, they will do so with fond memories of their youth.

Ski

1-24-2015